Tombstone and The Epitaph

John Philip Clum: We Need an Epitaph

John Clum was an Easterner who had come West in the 1870s, looking for opportunities - like so many others. Experience as a meteorologist, Apache agent, lawyer, and newspaperman prepared him for the biggest challenge yet: Tombstone, Arizona Territory, where he arrived in January 1880.

Within five months, on May 1, 1880, Clum had started a newspaper in the silver boom town. "No Tombstone is complete without its epitaph," he proclaimed in the initial issue, giving the publication its distinctive name which lasts to this day.

Tombstone was torn politically, socially, and economically. Clum and The Epitaph were Republican, representing business and town interests. The newspaperman was elected mayor in 1881; he also served as postmaster and head of the local vigilance committee.

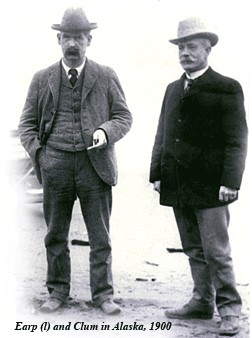

Clum was a good friend of the Earp faction in the ongoing difficulties with the so-called Cowboys, and The Epitaph's coverage of the October 1881 gunfight at the O.K. Corral (actually behind it) was one-sided. With three Cowboys dead and the Earp brothers walking tall, Clum immediately concluded, "EARP BROTHERS JUSTIFIED." With references to "the best class of citizens," to "all good citizens," and to "the better portion of our citizens," Clum’s view of the matter was settled.

But things didn’t work out for Clum; by mid-1882, he’d had enough. He had lost a wife, a daughter, and, in an undignified move by superiors, his job as postmaster. With his term as mayor also over, Clum was left with The Epitaph, which he sold – ironically, to some of the political opponents he had fought since arriving in Tombstone in 1880.

Tombstone was on the decline, especially by 1887 when water flooded most of the local mines. As the town struggled to survive, The Epitaph passed through many ownership hands and was led by many editors. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that the newspaper, and Tombstone, had a brief resurgence.

The Kellys and Helldorado

Two men named William Kelly – father and son – owned The Epitaph between 1926 and 1930. The younger Kelly was among the first to sense that Tombstone’s future might be found in the town’s history and setting instead of its flooded and dormant mines. In 1929, the town celebrated the 50th anniversary of its founding. "Helldorado," drawn from the title of a book by former Cochise County Deputy Billy Breakenridge, was the name given to the event. The Epitaph and the city underwrote the cost of the event, which was both popular and marginally profitable. It even drew Epitaph founder Clum, who quipped that he was "armed only with a fountain pen – sometimes the mightiest of weapons."

For its success in drawing attention to Tombstone’s place in the history of the Old West, Helldorado was not enough to keep Tombstone from economic decline. The economic, demographic, and political centers had shifted away from Tombstone and toward nearby Bisbee. It would be another 35 years before The Epitaph saw a resurgence.

Tombstone and Beyond…

In 1964, Detroit, MI, investors, headed by attorney Harold O. Love, purchased The Epitaph along with several other landmarks in Tombstone, including the O.K. Corral, the Crystal Palace, and Schieffelin Hall.

In 1974, Love and his colleagues began planning a new edition, a historical journal of the Old West. While it would never lose touch with its Tombstone roots, The Tombstone Epitaph National Edition would take the entire West in the second half the 19th century as its canvas. At the same time, the weekly Epitaph would continue to bring local news to Tombstone’s 1,500 residents. Then came a novel turn of events: the corporation met with the University of Arizona Department of Journalism to discuss a partnership whereby journalism students would produce the local edition. Journalism students continue to publish The Epitaph’s local edition on a biweekly basis during the school year, gaining practical experience in reporting and editing.

From Tombstone to Virginia City; from the "Last Stand" at Little Big Horn to the Massacre at Wounded Knee; from Pat Garrett to Billy the Kid; from Wyatt Earp to Pinkerton detectives; from the photography of C.S. and Mollie Fly to the Bassett sisters of Brown’s Hole, CO., the National Edition continues to bring a lively mix of stories and photographs drawn from the history and culture of the Old West.

The Tombstone Epitaph has seen and chronicled much of that history; it is the longest continuously published newspaper in Arizona. Sigma Delta Chi, the Society of Professional Journalists, has named it a national journalistic landmark. Thousands of people around the globe subscribe to the legendary paper, a recognition of its heritage and continuing quality.

In a very real sense, The Epitaph continues to embody the spirit and vision of founder John Clum. He couldn’t have foreseen the technological advancements of the past 50 years, the development of the Internet, social media, and other methods of distribution. But nearly 140 years after its start, the newspaper still tells interesting stories in a compelling fashion. In that regard, maybe The Epitaph is a misnomer. It’s not an end; it’s just a beginning.